Imagine that from the very beginning of the COVID-19 lockdown, when we switched from offices to meetings via teams or zooms, all our work-related activities became traceable. Information like how many hours we spent on the calls, how active we’ve been, how many comments we have posted (and what), how many times we presented our screen, what files we have shared… All this information are stored on the servers. I’ve checked it with a couple of DPOs from different brands, who confirmed to me that these data are stored, and tight internal policy rules protect that access. But I’m sure that even if you know that this data is not used in your company to control you, you will think twice before posting a chat message or sharing the file. You will think about your data privacy in your work differently.

From this example, we can take three lessons about data privacy and how consumers, in general, think about it:

- Phoney sense of control—data is something I provide to the company while filling the forms (like name, gender, email address); therefore, I can control what “they” know about me. When you have some more advanced user skills, you use more up-to-date techniques, like Adblock or incognito browsing mode, which gives an artificial sense of control;

- Denial, that all action leaves traces, a thinking dating back to the old Internet days—people change their decisions and behaviours if they realise that this data can be used against them in the future;

- Audience bias—there are good guys and bad guys like for teenagers, who openly share their lives on social media, except their parents, employees towards employers and citizens towards the government. The choice of who is who is entirely subjective, based on your private judgements (your value system).

Adding to that the fourth truth: data are an asset, so I, as a consumer, can pay with them (although I don’t necessarily understand how this market really works), complete the picture.

Therefore, data privacy is a complex topic, hard to grasp since its core lies somewhere on the crossroad of technology, sociology, morality, and money (sometimes including greed). Big Tech brands steer our attention away from more essential problems, and regulators, typically lagging behind reality, are not so eager to solve the issue.

I consider it from two perspectives:

- What are the consumers’ statuses: subject or commodity?

- Do we protect the right thing? Focus on data input, not output.

What are the consumers’ statuses: subject or commodity?

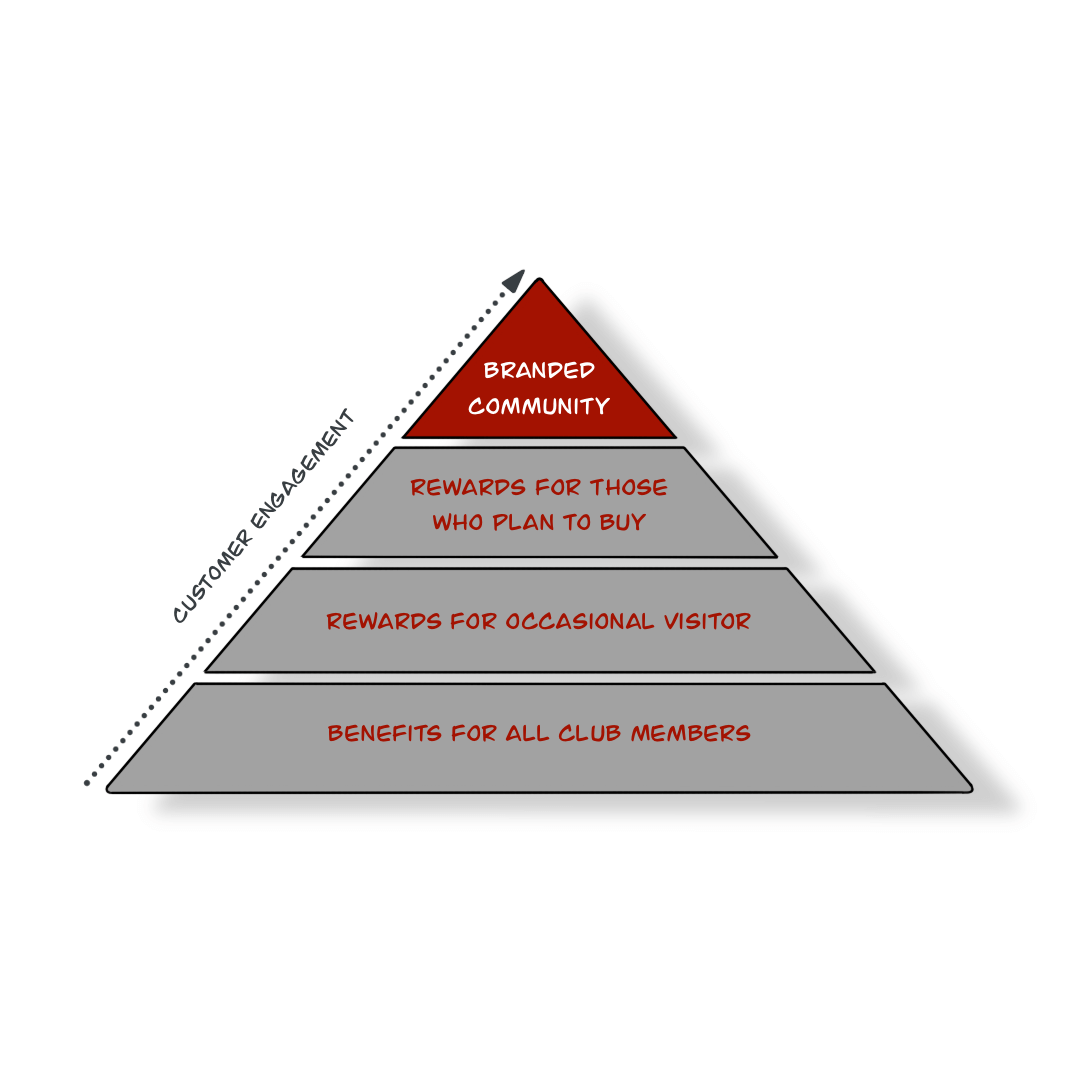

Human beings status is spread across two opposite edges. On one side of the scale, people are positioned as the subject of the relation with the brands. Marketers collect customers data to build direct relationships and serve them in a better way. On the other side of the scale, you can find humans perceived ad objects, commodities or merchandise. Social media and data platforms get access to your private life and put it on the stall to trade. The overarching goal is to keep your attention as long as possible because your time is a currency for advertisers.

What does it mean to privacy—in a partnership relation, consumers can understand the game’s rules and every significant modification requires their consent update. In the second—the rules are hidden, they change all the time, and the only choice you have is to love it or quit.

Do we protect the right thing? Focus on data input not output.

Regulators focus on protecting individuals and their identities. So our attention is redirected to the data input side: what data are collected and the purpose of using them. This part is highly regulated, which gives us the sense of control of who has access to our emails and declarative personal information (like name, gender, age, home address, kids etc.). As consumers, we are informed of what will happen with our personal information. Every data collection moment is preceded by informed consent, which, like a legal contract, sets the rules on the customer-brand line, where brands get as much information as the customer is happy to share. Customer data beyond this relation are protected, and brands have no access to them. Consumers can choose when they want to stay anonymous and when they want to be followed, and demand personalised treatment from the brands.

On the data output side, dominated by deep learning and artificial intelligence, everything slips out of control as, still, no one really knows how to regulate machine learning and AI. Big Tech doesn’t need your declarative information or get to know your identity because they know that the most important is not who you are, but what you do. Having access to the behavioural data of billions of people, gives them enormous study samples about how society works and what influences people’s actions. Fighting for your attention and time, they filtered the information to control your emotion and close you in your own bubble. By determining what you see and hear, they created a new reality, your own new privacy sphere. That influences your decisions far beyond the level of which product to buy or TV serial to see—it impacts your beliefs, lifestyle, life decisions, and the people you choose.

What does it mean to privacy? The biggest threat for consumers’ privacy comes not from what information we voluntarily share, but from how it will be used it on the scale. The challenge is that this part is driven by the more and more sophisticated algorithms and rapidly growing computing that really impacts how we think, and what we do is completely beyond control.

As in the example I shared at the beginning of this article, pandemics moved our lives from the cosy anonymous world to the new one, where every action leaves traces. With voice-controlled devices, Internet of Things consumers will be more and more helpless in protecting their privacy, maintaining their status as a subject of the relation and controlling the output—how their data are used on the scale.

But there is hope on the horizon that may come with Web 3.0. Evolution. Web 3.0, by its decentralised nature, will remove control of the internet from the centralised corporations that currently dominate it, helping internet users regain ownership of their personal data, which is a topic for a completely new article.